Venture capital drives innovation by funding early-stage startups, enabling rapid growth and technological advancements. Despite a higher risk profile, venture capital investments offer investors the potential for attractive returns by providing access to disruptive companies during their peak growth years.

Venture capital (often referred to as “VC”) investing has become a cornerstone of the financial ecosystem, providing crucial funding for innovative startups and early-stage companies. While traditional private equity investing typically targets mature, well-established companies with a history of success, aiming to enhance their operations and profitability, VC investing focuses on funding early-stage startups, often with unproven business models but high growth potential. This capital enables companies to rapidly expand their operations and growth, fostering innovation and technological advancements. The significance of this asset class in recent years is evident, as seven of the 10 largest publicly traded companies in the United States today — Apple, Nvidia, Microsoft, Alphabet/Google, Amazon, Meta/Facebook, and Tesla — were all venture-backed prior to going public. As technology continues to play a pivotal role in the global economy, transforming industries and creating new markets, venture-backed businesses are poised to remain key drivers of value creation. In return, investors can gain exposure to growth opportunities earlier in their development, potentially benefiting from returns that often exceed those available in public markets alone. Therefore, gaining some exposure to venture capital managers may be appealing for certain investors who meet the qualifications to do so and can tolerate the high degree of risk and illiquidity associated with the asset class.

This paper explores structural market dynamics that make VC investing attractive, examines its historical performance relative to other asset classes, and highlights the current market environment.

Key trends in venture capital

Over the past 20 years, the venture capital landscape has undergone significant changes. The asset class has grown to nearly $2 trillion1 today, which is over five times its size a decade ago and 18 times its size 20 years ago. In comparison, the Russell 2000 Index, a benchmark representing the U.S. small-cap equity market, has a total market capitalization of approximately $3.1 trillion. As the market has expanded and matured, the growing pool of institutional funding has enabled companies to remain private for longer periods. In its earlier days, venture-backed companies would raise funds in private markets, grow until their business model was viable, and then turn to public markets for additional capital to scale further. This transition typically involved an initial public offering (IPO), allowing a broader set of individual investors to participate in the company’s growth by purchasing shares when they first became available on an exchange. This process had generally occurred earlier in a company’s life cycle, giving public investors more opportunities to benefit from value creation. That’s changed.

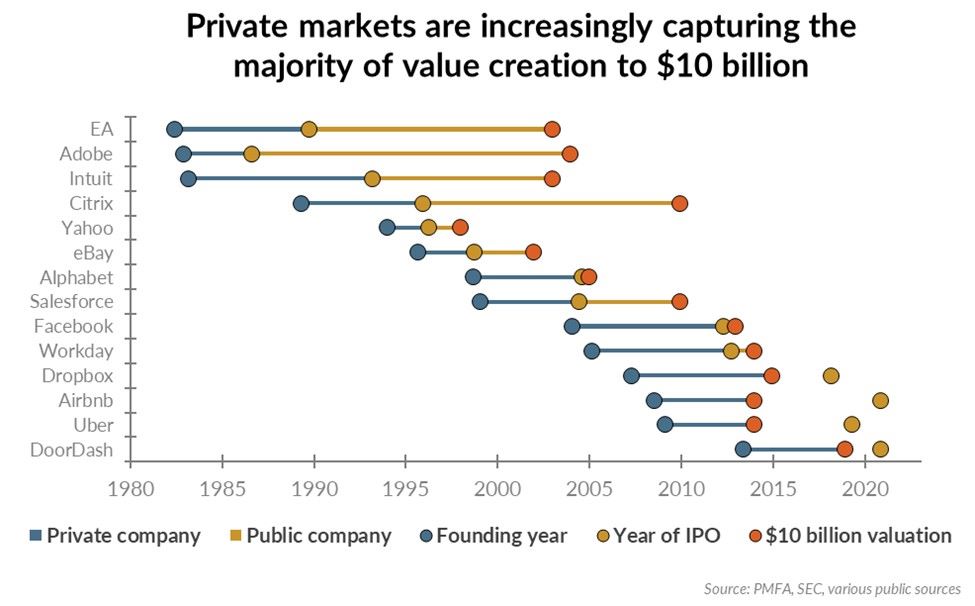

According to a recent study by Jay Ritter from the University of Florida’s Warrington College of Business, between 1980 and 1999, the median age of a private equity and venture-backed company at the time of its IPO was eight years. During this period, an average of approximately 307 companies went public each year. From 2000 to 2023, the median age at IPO increased to nearly 11 years, with an average of 127 companies going public annually2. This shift reflects the changing state of the VC market and the extended timelines for companies to reach the public stage. As such, many venture-backed companies are entering the public market as very large companies, rather than small caps that may grow into industry leaders over time. That timeline has meaningfully altered the investment opportunity set for investors that focus exclusively on public equities.

This structural shift is evident, as private companies are increasingly reaching much larger valuations (some even topping $10 billion) before entering the public markets. For example, major technology IPOs, Airbnb and Uber, waited over 10 years to go public, well after surpassing the $10 billion valuation mark and disrupting their respective industries. In contrast, Google/Alphabet and Salesforce went public much earlier in their life cycle, approximately five to six years after their founding.

The shift toward staying private for longer has arisen from several factors, including heightened regulation of public companies and the increased availability of private capital. One major regulatory development that has encouraged companies to stay private is the “Jumpstart our Business Startups (JOBS) Act.” Enacted in 2012, this law raised the “investor limit” for a private company from 500 to 2,000 investors, allowing companies to continue to access private capital without the cost and regulatory considerations associated with going public. Increased access to private capital allowed companies to postpone or completely avoid entering the public markets.

A notable outcome of this trend is the extended lifespan of venture capital funds, often necessitated by the time required to realize returns through exits, particularly for larger companies. According to a recent Pitchbook study3, the median holding period for venture portfolio companies with exit sizes of over $500 million was approximately six and a half years in 2010. By 2024, the median holding period increased to nearly nine years. Most VC funds have a stated lifespan of 10 years, but some may extend a few additional years, with or without investor consent, to manage remaining portfolio companies and finalize exits. The lengthening of the venture market holding period has brought greater attention to other liquidity options for VC fund investors, including secondary markets, continuation funds, and others.

While VC investing comes with a long-term investment horizon, it provides a unique opportunity for investors to access disruptive companies during their peak growth years. With the structural market dynamics taking place, the appeal of investing in venture-backed companies prior to their IPO has become increasingly compelling.

Performance observations of venture capital

Venture capital has historically exhibited a higher risk profile than that of other asset classes due to the early-stage nature of startups. VC funds are often investing in innovative or disruptive companies with high failure rates. As such, it’s not uncommon for VC funds to have loss ratios in excess of 20%, implying that at least one in every five portfolio companies will incur a loss on investment. Early-stage VC funds may have loss ratios that exceed 50%.

Conversely, those companies that survive and thrive often provide outstanding return potential for investors. For VC investors, diversification is critical. To offset complete losses on certain portfolio holdings and still deliver strong overall returns, a VC fund often relies on a few highly successful portfolio companies to carry performance. It’s the potential gains of those successful emerging companies that entice investors to invest in the asset class.

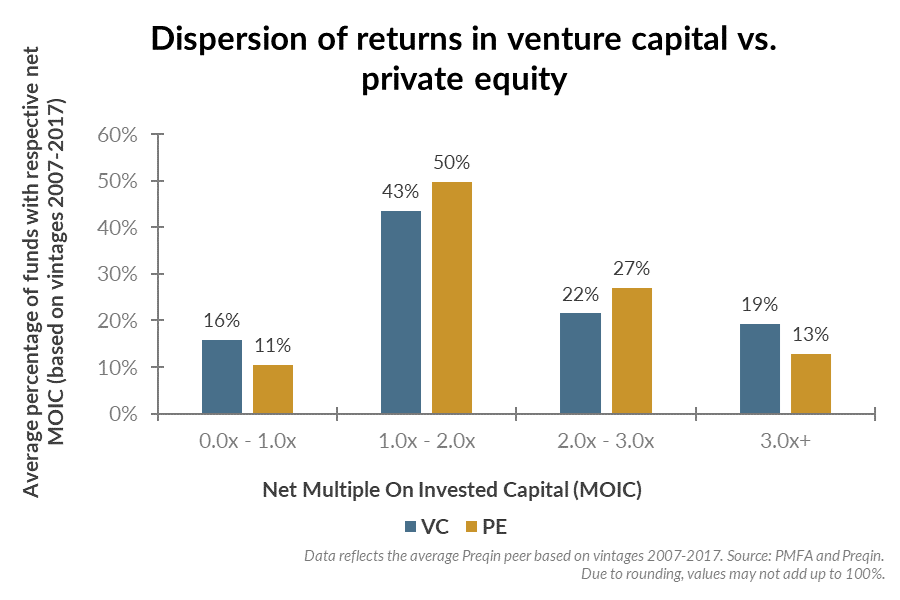

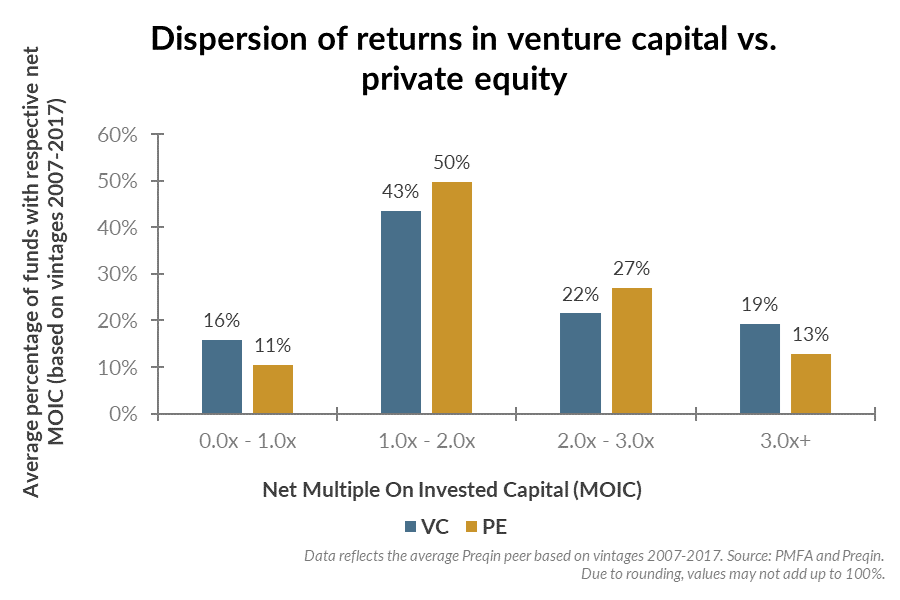

Given the high loss ratios within the VC space and massive gains on the most successful investments, return dispersion between the best and worst funds is extremely high relative to other asset classes. As shown in the chart below, there is both a higher percentage of VC funds that lost money (Multiple on Invested Capital (MOIC) < 1x) and achieved outsized returns (MOIC > 3x) when compared to private equity funds. This speaks to both the relative opportunity and critical importance of investing with top VC managers with proven track records rather than simply gaining exposure to the asset class. Further, it points to the benefit of investing in a variety of funds covering multiple vintage years to reduce risk associated with poor timing across market cycles or subpar investment results from a single fund or manager.

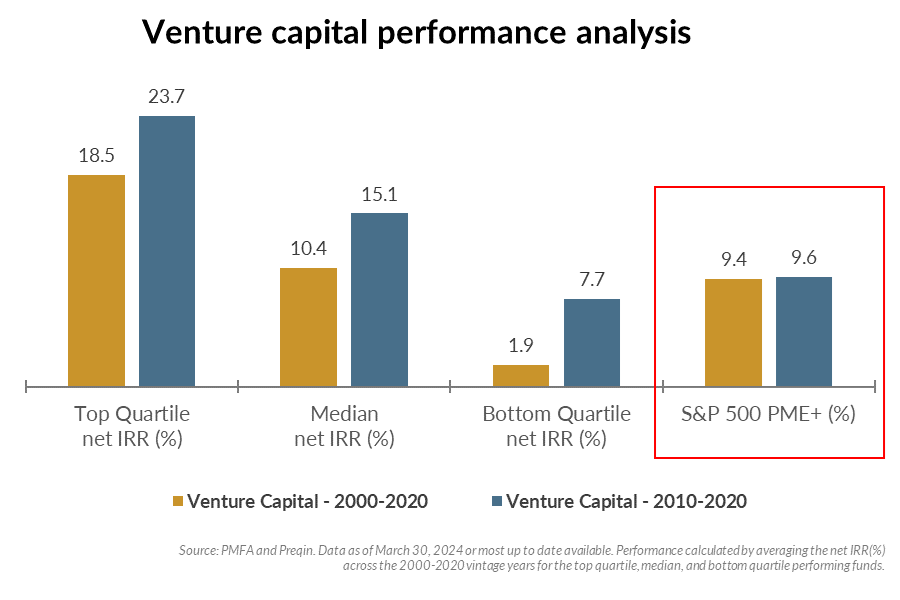

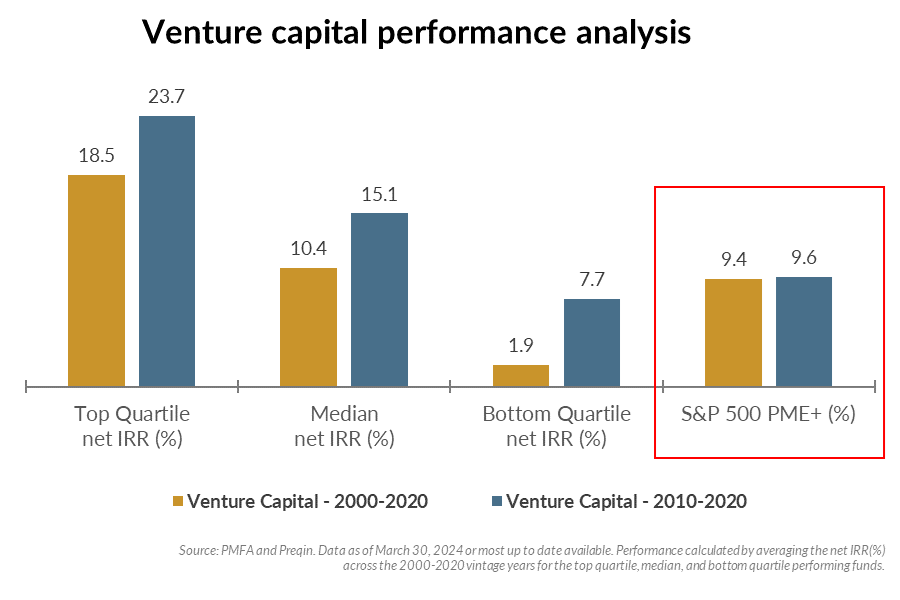

Compared to public markets, venture capital has historically provided a return premium over time, particularly for the top-performing funds. The performance of public indices and private capital can be directly compared using the public market equivalent (PME). This metric converts public returns into an IRR-like measure, accounting for cash flows. As shown in the chart below, from 2000 to 2020, the median Preqin VC fund achieved an average net IRR of 10.4%, while the S&P 500's PME+ was 9.4%. During the same period, the top quartile Preqin VC funds produced an average net IRR of 18.5%, significantly outperforming the S&P 500’s PME+ Index. The outperformance of top quartile Preqin VC funds versus the S&P 500 PME+ was even more pronounced between 2010-2020, which excludes both the frothy investment environment of the dot-com bubble period of the early 2000s and the extremely challenging exit period during the Global Financial Crisis.

Because of the exceptionally wide range of performance among VC managers, investing with top-tier managers who’ve demonstrated consistent returns is critical. In addition, investors should diversify across different vintage years and managers to reduce portfolio risk and potentially smooth their return stream. The size of a VC allocation should also be carefully considered within the context of a private equity program to mitigate risks.

Current market environment for venture capital

On the back of low interest rates, fiscal stimulus, and a rapid shift to digital adoption during the pandemic, VC valuations reached peak levels in 2021. As the Federal Reserve began raising interest rates in 2022 and investor sentiment shifted, the VC ecosystem experienced significant valuation markdowns and the lowest exit activity in a decade. As a result, companies faced a dramatic drop in venture funding. Later-stage or pre-IPO companies were the most significantly affected by these factors, in many cases, delaying VC managers’ ability to move forward with anticipated exits.

The current venture market mirrors past slowdowns, such as those that accompanied the dot-com bubble and the Global Financial Crisis, with declining valuations, slower capital deployment, and reduced exit activity. Despite these challenges, historical trends suggest that these market downturns often precede some of the strongest VC vintages. Post-slowdown periods typically offer more attractive entry valuations and reduced competition for deals due to softer investor interest.

While the market has faced significant headwinds, early signs of recovery are emerging. The rebound in public equities has positively impacted private company valuations. Additionally, the Federal Reserve’s recent interest rate cuts have been expected to create a more favorable environment for IPOs and M&A activity, lowering the cost of debt. Questions still persist; however, as the Fed recalibrates its interest rate projections given sticky inflation, stronger-than-expected growth, and significant uncertainty related to trade and immigration policies and their potential economic impact.

From a structural perspective, investing in technology and startups, especially those focused on artificial intelligence (AI) and digital transformation, has driven investor enthusiasm for both private and public companies that appear well positioned to benefit. Significant advancements in these areas are driving the creation of new business models and opportunities. Generative AI stands out as one of the most promising fields, with many investors considering it the most exciting technological development since cloud computing, smartphones and other mobile devices, or even the internet itself. OpenAI’s release of ChatGPT on Nov. 30, 2022, marked a pivotal moment in the AI landscape, rapidly bringing generative AI into the public eye. Since then, we have witnessed rapid adoption and unprecedented capital expenditure across the AI ecosystem. As AI opportunities continue to evolve, their disruptive potential may make them a compelling investment opportunity through the venture channel.

The bottom line

For qualified investors willing to accept illiquidity, tax complexity, and other risks, venture capital remains an attractive investment opportunity due to its potential for strong returns, strategic advantages of companies staying private longer, and favorable current market conditions. As technological advancements continue to reshape industries, venture capital is well-positioned to fund innovation and drive economic growth.