As M&A transactions become more complex, the timing and valuation of accounting and tax treatments for these deals become subject to an increasing number of variables. In our previous article, we looked at how earnout provisions can affect the financial results of the acquired business and also explained some distinctions between earnouts qualifying as compensation and those treated as consideration in calculating the purchase price of the transaction. Here, we’ll review how contingent consideration treatment can affect the buyer’s accounting and tax calculations at the time of the deal and in the periods following the agreement as the post-transaction business achieves or falls short of the milestones set in the contract.

Accounting challenges for contingent consideration: Equity vs. liability

A big challenge presented by contingent consideration is determining if it should be carried on the acquirer’s books going forward as equity or a liability. This is a critical decision because the buyer’s subsequent income during the contingency period may be directly impacted by this classification. Consider these differences between liability classified and equity classified arrangements:

- Liability classified arrangements are remeasured at fair value at each reporting period with changes recorded through income until the contingency is resolved.

- Equity classified arrangements aren’t remeasured after the initial transaction date.

Given the potential for significant impact to the income of the buyer subsequent to the transaction, it’s important that any transaction not settled in cash should be analyzed thoroughly for classification in advance to avoid any unexpected results. This is especially true for those earnout arrangements with significant maximum amounts (or no maximum) and longer contingency periods.

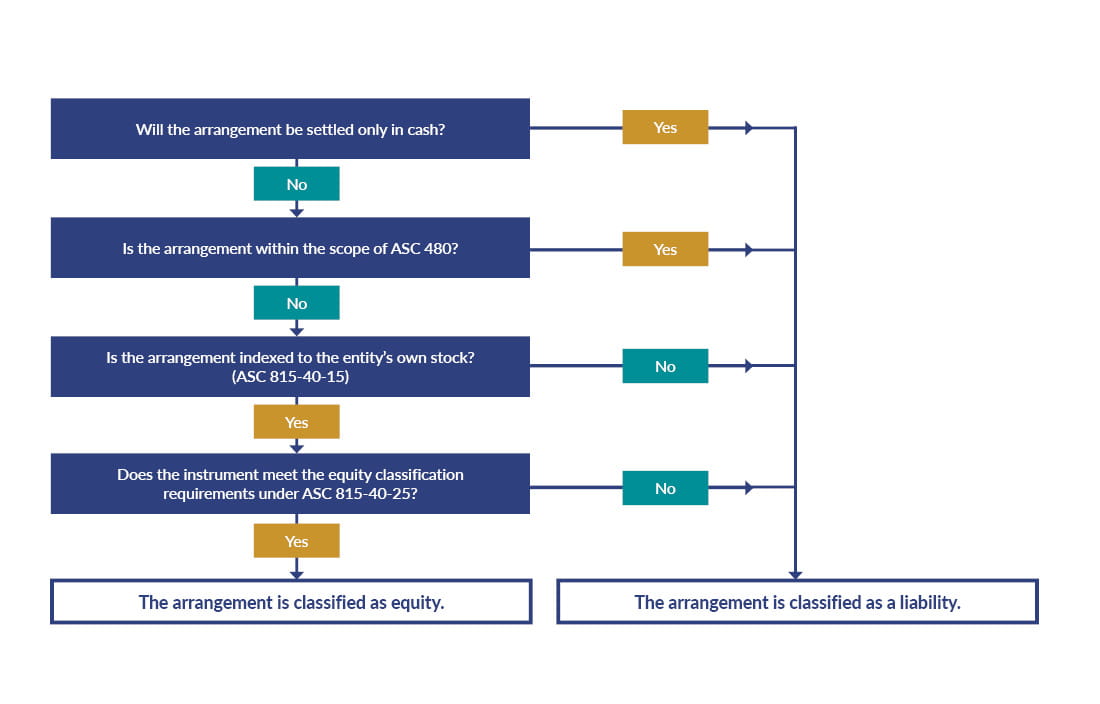

The flowchart below illustrates the series of questions that must be answered in order to make this determination:

These three questions will help a buyer to properly classify the transaction:

- Will the arrangement ultimately settle in cash? So many of today’s deals ultimately settle in cash, even if they are contingent on future performance. For example, if earnings in two years are $x, the seller receives cash in the amount of $y. If EBITDA reaches $x level, the buyer agrees to pay the seller $y. These terms make for a fairly straightforward classification of the payment as a liability because of the cash settlement.

- Will the arrangement involve the issuance of equity securities? If so, first analyze under Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) 480. If the transaction involves the issuance of equity securities to the seller, those securities must be analyzed under ASC 480 to determine if they must be classified as a liability on the buyer’s balance sheet. If the arrangement doesn’t meet ASC 480 criteria as liability, it’s subject to further analysis before a conclusion can be reached.

- If the security isn’t a “liability” within the scope of ASC 480, does it meet the criteria for equity classification under the derivative guidance in ASC 815-40? Assessing the guidance in ASC 815-40 can be challenging and cumbersome. Overall, if the arrangement is both indexed to the entity’s own stock and meets the criteria for equity classification as more thoroughly described in ASC 815-40, it will be classified as equity in the buyer’s financial statements. If these criteria aren’t met, it will be classified as a liability.

The key takeaway here is that an acquirer and a target have every opportunity to structure the deal in advance to get the treatment that best serves both parties. Many deals involve settling significant portions of the sale price in cash, leading the parties to assume liability treatment. But the inclusion of even a portion of the contingent consideration that could be settled in equity can trigger significant complications.

Role of the legal obligor in a liability situation

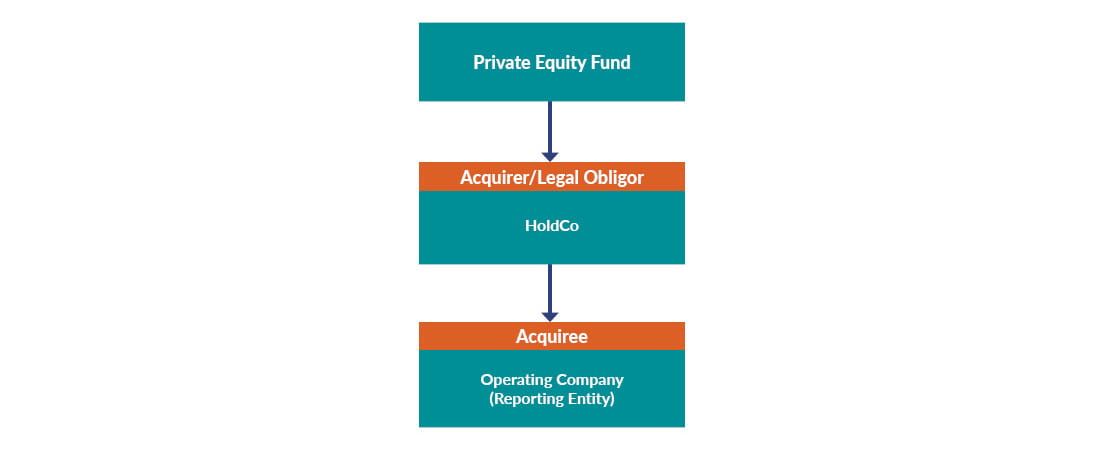

It’s also important to understand who the legal obligor is for the contingent consideration when determining the proper classification. If the contingent consideration is classified as a liability, the reporting entity must be considered a “legal obligor” to record the liability. The legal obligor for equity instruments or cash settlement of the contingent consideration may be a parent company of the acquirer reporting entity — or, the reporting entity may be applying pushdown accounting to the acquiree who isn’t legally responsible for payment of the earnout. In these cases, the contingent consideration liability wouldn’t be reflected in the reporting entity's financial statements in the year of acquisition or thereafter.

For example, consider a situation where the acquirer is a holding company (HoldCo) created by a private equity fund and the reporting entity is the acquiree (applying pushdown accounting). If the transaction includes contingent consideration to be paid in cash by HoldCo to the seller based on a revenue target, that would generally be a liability of HoldCo and not of the reporting entity. As a result, the reporting entity would recognize the fair value of the contingent consideration at the transaction date as an equity contribution from HoldCo in its financial statements rather than a liability. Because the reporting entity is not recording the liability, it also wouldn’t reflect the future changes in fair value of the contingent consideration in its financial statements.

Tax challenges for contingent consideration

Although the tax treatment isn’t dictated by the GAAP treatment, there are similarities. For example, assuming that it has already been determined that the amount is an earnout and not compensation, a taxpayer still needs to determine whether the contingent consideration will be considered additional equity, payable in cash, or some combination of both. Depending on the answer, the additional amount could be considered additional purchase price or rollover with carryover basis. Like many areas of tax, the treatment is dictated by the facts and circumstances, not a particular bright line test or set of factors.

Once a taxpayer has identified whether the amount is going to be additional equity or cash purchase price, they must still determine when the amount is includable for tax. At closing, a purchaser is typically waiting for future events to trigger the inclusion of the earnout amount. Usually, a cash amount is fixed when paid but could become fixed before the item is actually paid if circumstances fix the liability earlier.

Once the payment becomes fixed, it will be an additional consideration for tax purposes. For cash purchase price, the taxpayer typically layers the amount into purchase price and basis. For example, in an asset acquisition, the additional proceeds will be allocated to the assets, often as goodwill, and amortized over the remaining months of the original 15-year amortization period. Whereas in a stock acquisition, the additional proceeds would result in an additional stock basis. There are many other variations in treatment depending on the transaction, but generally, additional consideration from earnouts will be treated in the same manner as the original consideration.

Because the earnout amount is deferred, an interest component of the eventual payment should be considered. Rarely do earnouts overtly acknowledge interest, but a taxpayer should specify the terms in the agreement to identify an appropriate amount of interest. The interest amount could have a material impact on taxable income, although a buyer might already be limited in how much interest they are able to deduct.

Valuation of contingent consideration

According to the latest AICPA guidelines, contingent consideration arrangements should be measured at fair value as of the acquisition date. An accurate fair value determination requires a thorough understanding of market conditions on the acquisition date and the specific contingencies outlined in the purchase agreement. Some of the key terms of the contingency that must be analyzed include:

- The structure of the agreement

- The likelihood of achieving performance targets

- The associated financial impacts

For example, if the financial results of one measurement period will impact the calculated payment in another period (a condition known as “path dependency”), it’s possible that parties might need to use a different valuation methodology than a single period linear structure.

Once the market conditions and the conditions are understood, techniques such as probability-weighted analyses and the use of option pricing models are commonly employed to estimate the fair value of these contingencies.

The AICPA’s guidance aims to ensure a standardized approach, enhancing consistency and comparability across financial reports — ultimately aiding in providing transparency for stakeholders. The Institute emphasizes that the fair value measurement must incorporate all available information at the acquisition date and should reflect the perspective of market participants. Once the contingent consideration is valued and included in the balance sheet as a liability, subsequent changes in the fair value of the contingent consideration will have an impact on earnings that could lead to potential volatility in post-acquisition financial statements. Therefore, accurate initial valuation and continuous reassessment are crucial.

Valuation models for contingent consideration are trending toward the option pricing method (OPM). Recent guidance from the Appraisal Foundation suggests that this method is the most reliable alternative for three reasons:

- OPM analysis provides more transparency of key inputs that makes the analysis more auditable.

- OPM analysis adjusts for risk more effectively when compared to a scenario-based methodology.

- OPM analysis promotes a much more consistent process for providing these valuation analyses.

The key under any circumstance is for the seller to communicate with the auditors early to develop a plan for valuation of contingent consideration that everyone can agree on and understand.

The seller’s side is just the beginning

Contingent consideration will, by design, continue to impact the obligations of buyers and sellers beyond the closing date of any transaction. Its inclusion in the terms of a deal can help to provide assurance to the marketplace that the parties have taken effective steps to support post-merger continuity. However, inadequate assessments of the value of the contingent consideration provisions can result in post-transaction financial statement uncertainty. In order for the parties to get the full benefit of the contingent consideration, everyone involved needs to commit to accurate assessment of market conditions and the terms of the contingencies at the time of the deal, as well as continuous reassessment of their ongoing value.