In summer 2024, the U.S. Supreme Court decided Moore v. United States, a case that received considerable attention from tax professionals. The attention was driven both by the specific question involved and the case’s potential to shake the very foundations of the U.S. tax system. While ruling in favor of the government, the Court ultimately didn’t realize its destabilizing potential. However, a central question of whether realization is a constitutionally required feature of federal income taxation remains an open question. Here’s a closer look at the Moore decision and its potential significance in the months and years to come.

- Placing Moore in the broader context

- What did the Court say in Moore?

- What are the immediate consequences of Moore?

- What consequences might follow from Moore in the future?

- So, what does all of this mean?

Placing Moore in the broader context

Understanding Moore and its reasoning begins with its place in the tax landscape. Historically, the United States has applied a worldwide system of income taxation. This generally meant that its taxing power extended to all sources of income recognized by U.S. citizens and residents. Importantly, that included both foreign-source income and domestic-source income. This is in contrast to a territorial tax regime, which would typically limit taxation to domestic-source income. There were exceptions to the worldwide system and the application of foreign tax credits partially mitigated double-taxation concerns.

Subpart F is a long-standing feature of U.S. international tax that deals with controlled foreign corporations (CFCs). In the years prior to 2017, Subpart F typically allowed U.S. multinationals to indefinitely defer U.S. tax on foreign income by placing CFCs into their entity structures. Such entities would pay tax in the foreign jurisdiction, but U.S. tax wouldn’t be paid until the earnings were repatriated to the United States through a dividend. Certain types of income weren’t eligible for deferral under Subpart F (e.g., insurance income and foreign base company income). However, these rules resulted in the estimated accumulation of trillions of dollars in foreign earnings that hadn’t been subjected to U.S. taxation.

The situation became more complex in 2017 through the enactment of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). That law shifted the U.S. tax regime toward a more territorial tax system. The TCJA also included a so-called “transition tax,” codified in Section 965 of the Tax Code. That tax directly confronted the potentially limitless tax benefits on foreign earnings that had accumulated within CFCs. Specifically, Section 965 subjected U.S. shareholders of deferred foreign income corporations to a one-time deemed repatriation of their deferred earnings, subject to special tax rates and payment schedules.

Moore was a test case about realization, and the test concerned Section 965. The Moores are a U.S. couple who invested in a CFC back in 2006. The CFC generated foreign earnings but never made distributions to the Moores or the other shareholders. When the TCJA version of Section 965 became effective, the Moores paid their pro rata share of the tax on the deferred earnings and then sued for a refund. They argued the 16th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution requires income to be realized before it can be subjected to U.S. federal income tax. Since the CFC hadn’t distributed its earnings to them, they argued that the transition tax was unconstitutional.

What did the Court say in Moore?

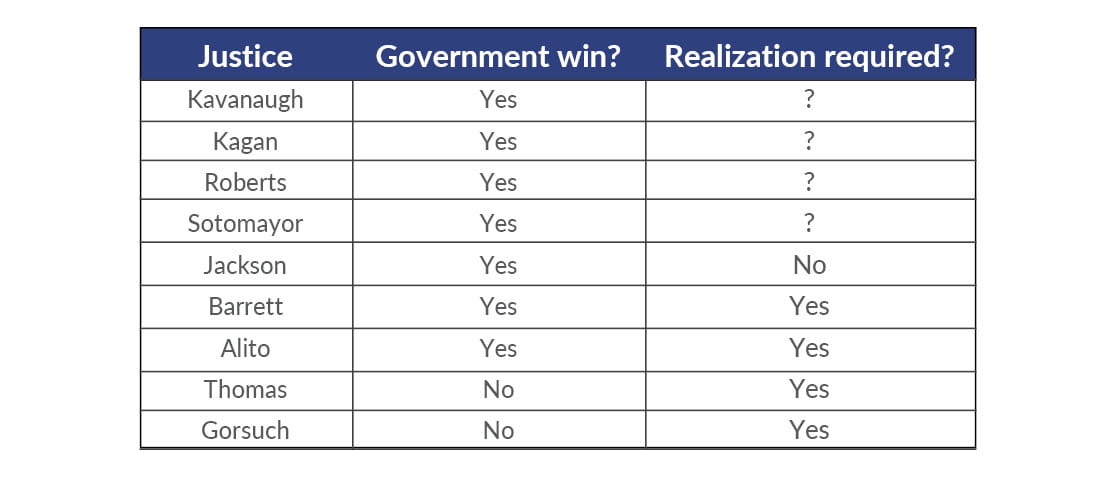

In simple terms, the Court upheld the Section 965 transition tax. However, the Court didn’t speak with one voice, especially on the question of whether realization is a requirement for taxation. Moore is a roughly 80-page decision containing four opinions that may be summarized in briefest terms with a table:

This table captures the nuanced takeaway from Moore. The case was technically decided 7-2 in the government’s favor on the question of the constitutionality of the transition tax. However, the question of whether realization is a constitutional requirement is much more complicated. At least four justices understand realization to be required, one has a contrary understanding, and questions remain for the balance.

Majority opinion

The majority opinion (Kavanaugh, Kagan, Roberts, and Sotomayor) saw Moore in terms of what it called “attribution.” The majority said Congress has the power to attribute an entity’s realized, undistributed income to shareholders, and then tax that attributed income. The opinion assumed without analysis that Section 965 involves entity-level realization. This assumption means it remains somewhat unclear how attribution effectively differs from deemed realization. In other words, where Congress forces or deems realization at the entity level, and then that realized income is attributed to shareholders, it’s still somewhat unclear how to distinguish between forced realization and attribution.

The majority focused on some very old cases it said establish that Congress has the constitutional power to tax certain corporations. These cases mostly did not figure meaningfully in the briefing. And the one case that was a fixture in the briefing, Eisner v. Macomber, 252 U.S. 189 (1920), was brushed aside by the majority because of what it did not have to say about attribution. Macomber is understood by many, fairly or not, to have established a realization requirement.

Justice Jackson, concurring in full

Justice Jackson joined the majority’s opinion that Congress has the constitutional authority to “attribute” income by taxing shareholders on a corporation’s undistributed income. She wrote separately to directly address Macomber and express her view that the case is “outmoded, if not overruled.” Largely for this reason, Jackson concluded the constitution doesn’t require realization, meaning capital and income don’t need to be separated before income is taxed.

Justice Barrett, joined by Justice Alito, concurring in the judgment

Justice Barrett’s opinion went the other way in substance, even though it’s also a concurring opinion. Barrett concurred in the majority’s judgment because of her understanding that the case presented both realization and attribution questions and because she agreed with how the majority decided the attribution question. But Barrett took the majority to task for avoiding the realization question and made plain her perspective that the 16th Amendment does, in fact, require realization. Her thinking had to do with how she reads Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan & Trust, 157 U.S. 429 (1895), an old U.S. Supreme Court case that was, for Justice Barrett, only partly overruled by way of the 16th Amendment. Her thinking also had something to do with her reading of that Amendment, which uses the word “derive” to describe Congress’ taxing power. Because the text of the 16th Amendment says Congress can tax “incomes, from whatever source derived,” and because “derived” is tantamount to “realized,” it followed syllogistically for Barrett that realization is constitutionally required.

Justice Thomas, joined by Justice Gorsuch, dissenting

Justice Thomas agreed in dissent with Justice Barrett’s take on realization. He, like Barrett, understood the word “derived” to be a “near synonym” for the word “realization,” and like Barrett, took a great deal from the history behind Congress’ taxing power and the 16th Amendment. Thomas also took pains to explain his view that increases in value aren’t “income.” This can easily be read as telegraphing his understanding that a wealth tax would be unconstitutional. But Thomas was even less forgiving than Barrett when it came to the majority’s decision to avoid the realization question the Court took Moore to answer. If the “attribution” rule seems new to you, then you aren’t alone: Justice Thomas considers the rule to be new and without basis in the Court’s precedent.

What are the immediate consequences of Moore?

Ultimately, Moore preserved the U.S. tax system’s status quo by upholding the constitutionality of the transition tax. No immediate practical consequences follow directly from the decision.

Some taxpayers may have filed protective refund claims in the hopes of a different outcome in Moore. The IRS will deny those claims. Some taxpayers opted to pay their one-time transition tax liability in installments over a period of up to eight years. To the extent any installment payments might remain, they will need to be paid as previously scheduled.

What consequences might follow from Moore in the future?

While Moore preserved the status quo, it also suggested a series of potentially significant open questions. No one has clear answers to the foundational questions intimated by Moore. Still, the decision read carefully in the light of some established constitutional and tax concepts provides some insight into what direction we are likely heading next. The following questions will likely be at the center of tax controversy and planning in the years to come.

Is there a constitutional realization requirement?

The Court agreed to answer this question — does the 16th Amendment authorize Congress to tax unrealized sums — when it granted certiorari. While we don’t have an answer, we do have at least four votes on the Court for a realization requirement. And we know those votes are grounded on multiple reasons and lines of thinking.

Overall, the opinions generally express awareness of the stakes. The Justices tested both sides during oral argument about the consequences to hallmark features of the U.S. tax system if they were to hold realization is constitutionally required. The majority mentions the “trillions in lost tax revenue” that might follow from such a holding. That view is shaped by an understanding that there are no meaningful distinctions between Section 965 and the taxation of partnerships and S corporations. Thus, a U.S. Supreme Court decision saying the constitution requires realization could crack the income tax’s foundation.

But, a future decision may not need to fully undermine the tax system. It’s easy to imagine a world of constitutional law where realization isn’t a categorical requirement. It could be one of many constitutional rules that admits to exceptions. The First Amendment, on its face, speaks in absolute terms. But it’s certainly not understood in an absolute way. Could this happen with the 16th Amendment? Again, there are at least four votes for a realization requirement, and it takes at least four votes for the Court to take a case. In the future, the Court could find that while realization is generally required as a matter of constitutional law, the Amendment allows for exceptions out of consideration for Congress’ broad taxing power and for individuals’ due process rights.

What is an income tax?

Many people expected Moore to have a lot to say about what “income” truly is. Section 61 of the Code loosely defines gross income and reflects, in broader economic terms, a Haig-Simons understanding of the concept. Many learn the term with reference to Commissioner v. Glenshaw Glass, 348 U.S. 426 (1955), which includes a “clearly realized” component.

If these were our best answers before Moore, then they probably remain so. Some of the most basic questions are the most difficult, and Moore on the whole reads like a critical number of Justices avoiding one. But that doesn’t mean the question will not come up again. Justices Barrett and Thomas both expressed their perspectives so strongly and in so much detail that they could easily be repurposed as briefs for future taxpayers.

And how does it compare to an excise tax?

The government styled Section 965 as an excise tax in its brief. There were interesting exchanges at oral argument on the transition tax’s nature. Some involved Justice Jackson, who wrote specially on the excise tax angle. The significance of this angle has to do with the fact that Article I of the constitution carves out excise taxes from the apportionment requirement. So, what is the true nature of an excise tax? Does it have to be transactional, like a consumption tax? Is it imposed on certain kinds of privileges? Does it have more of a regulatory purpose and function than other kinds of taxes?

These are mostly open questions. The Court recently passed on its opportunity to answer a similarly enticing question by denying certiorari in Quinn v. Washington. Quinn would have given the Court the opportunity to expand on the nature of the excise tax. Even still, there is some case law in this area, such as Flint v. Stone Tracy Co., 220 U.S. 107 (1911). So, the Court wouldn’t have to clear an entirely new path if it were to walk in this direction.

How does due process define the limits of retroactive taxation?

The Moores argued in the lower courts that, beyond the 16th Amendment problem, Section 965 creates due process problems. Even though the Moores didn’t seek certiorari on the due process question, it got some attention during oral argument. The question matters in this context because Section 965 goes back roughly 30 years to capture retained earnings. And because there is a case — United States v. Carlton, 512 U.S. 26 (1994) — that places some due process limits on retroactive taxation. But how many years are too many for due process purposes? Moore didn’t answer this question but could have — and the question will likely be presented again, especially outside of the 9th Circuit, where Moore originated.

And what about a due process limiting principle for income attribution?

Moore stands for the proposition that the government can, consistent with the constitution, attribute income realized at the entity level to a shareholder. We probably also know that this attribution principle can work in related ways the Court found to be conceptually indistinguishable. These apparently include, at minimum, partnerships, S corporations, and subpart F generally. The majority opinion went further and clarified that “due process proscribes” arbitrary attribution. Justice Barrett agreed. So, if we were to add on to the above table, we would count at least six votes for the idea that due process places some limit on the government’s power to attribute income.

But those limits are left undefined in Moore. They remain unclear partly because, as noted above, the Court also didn’t do much to help us think through how to identify which taxpayer — the entity or the shareholder (or partner, or member, etc.) — realizes income in a situation where the answer is somewhat unclear. The Court only provided that so long as only the entity or shareholder realized the income, and not both, attribution is proper. Again, Section 965 operates in a way that appears, from a certain perspective, like pass-through entity taxation. Beyond this, as Justice Thomas notes, Section 965 contemplates a strange relationship between ownership and tax. A shareholder’s Section 965 liability could extend to years before the year in which the shareholder had a CFC ownership interest.

So where does realization end and begin? Where are the limits of attribution? These basic questions do not have clear answers, but we do have some established due process principles that could potentially guide future decisions. There is the idea, applicable in other contexts, that the government can’t take property under laws too vague for ordinary people to have notice. This protects against arbitrary enforcement and allows people to predictably conform their actions to law. And there is the idea that where the government deprives someone of a property right, it must in a somewhat timely way provide a hearing on the appropriateness of the deprivation. This combination of principles could drive some of the tax controversies that are sure to follow Moore.

What does uniformity require exactly?

Taxes must either be direct or indirect. Indirect taxes need not be apportioned, but they must be “uniform.” Moore doesn’t speak to this term’s meaning, but the way in which the Court walked through some first principles of income taxation suggests the term’s potential importance. Thomas noted some older cases he said indicate the term carries a geographic meaning. Those who are interested in state and local taxation know many state constitutions impose a uniformity requirement. In the state tax context, these requirements operate much like the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause. But what does uniformity mean for federal income tax purposes? We’ll have to wait for an answer to this question.

What about an actual wealth tax?

This is the question that has loomed over Moore since the Court agreed to take it. A wealth tax could take one of several forms, and Moore helps us understand what those forms might be. The majority identifies three in footnote 2: (1) taxes on both the entity and its shareholders on undistributed income; (2) a tax on holdings or wealth directly; and (3) a tax on appreciation. If a wealth tax were to take the form of a mark-to-market tax on accumulated capital, then it would be analogous to at least one Tax Code provision. Section 877A taxes high-income earners and high-net-worth individuals on a mark-to-market basis when they exit the U.S. tax system. If a wealth tax were a “direct” tax on capital, like ad valorem state-level property taxes, then the tax would need to be apportioned.

The Court observed in Moore that such direct taxes have been historically rare to the point of nonexistence because of the apportionment requirement. Several justices offered opinions about taxing the appreciation of some kind of economic value. Justice Jackson’s opinion strongly implied her view that a “wealth” tax — a tax on capital, before income is separated from it — would be constitutional. Barrett, for her part, implied such a tax wouldn’t be constitutional because, as she put it, appreciation isn’t income. But the majority expressly reserved the question of an unapportioned tax on appreciation. Going forward, we might reasonably expect that the votes for realization in Moore would also be votes against a wealth tax, if one were to ever be enacted and subsequently challenged before the Court.

So, what does all of this mean?

As noted above, the direct consequence of Moore is a simple clarification that the transition tax implemented under Section 965 by the TCJA is constitutional. Beyond that, we’re left with tantalizing, but unsatisfactory, clues about the Court’s view of realization as a constitutional requirement for taxation. This case was also decided during an election year in the context of public debate over proposed wealth taxes. Moore doesn’t provide a simple answer about the constitutional parameters of such taxes. In that sense, this case may be read as an opening act in the story that will unfold over the coming years.